Having been associated with medical device development directly and tangentially for many years, I have witnessed and used a few things that make a difference. I would like to share these with you so that the collective wisdom of me and my colleagues can help you in your effort to bring your product to market. Hopefully, these hints will help fill in the gaps from other “Medical Device Development Tips” or “Top 10 Lists” that you may have seen elsewhere:

1. Do you know your insurance reimbursement code? Then please tell us!

A hallmark of the most efficient and serious players in the medical marketplace are those that have established what their device’s insurance reimbursement code will be. They have done the challenging work of talking to the insurance companies, the medical community and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and hammered out an understanding. If you have a code, then you have a value proposition and that is the heart of any good business plan. A better “mouse trap” is only better if catches mice and saves somebody money somewhere.

It is important to share this insight with your product development partner. If your design team understands why your product is better than the other guys, they can help to enhance that aspect of the design. An efficient design that speaks to the underlying need is essential and a competent design team may need to push back if creeping elegance threatens the primary design function.

2. Medical prototyping is not like regular product prototyping.

Creating a prototype of a medical device can be a challenge, especially when considering catheters and other invasive, skin contacting, or even implantable components. You can’t just use any available material that the 3D printer has loaded up or that the machine shop has on hand. You should use “real” materials as soon as the proof-of-concept phase has passed. It may be acceptable to use non-certified resins and metals in early prototypes if they will not have human contact or be used in studies, but why would you choose to add an element of doubt into the analysis and behavior of your precious creation?

Medical devices often rely on special processes as well. For instance, if you consider catheters what odds do you give of finding an occluding balloon of the correct diameter and length off-the-shelf? Who knows, you might get lucky and find a source but in general it is better to start developing a production partner you can rely on. So, for medical devices, getting the right parts in the right materials with the right processes will take longer. These longer cycles should factor into your resource and schedule planning.

3. If you did not engage UX in the product architecture, you may be in for a bumpy ride.

The FDA requires human factors usability testing for devices. Not only is it a requirement, but it is also a great idea to embrace this requirement early. If, in the architecture phase, your user experience (UX) designer can help identify and mitigate the potential use hazards and risks, you may be able to simplify the workflow and product requirements. This thereby reduces the device complexity and can make your product safer.

Also, if you determine the need for built-in mitigation such as special circuits, interlocks, or labeling, then you can incorporate the required features into the early product development phases in which such changes are more easily made. Can you imagine the scheduling headaches caused by having to add a lock-out slide control widget to a tooled-up injection molded handle?

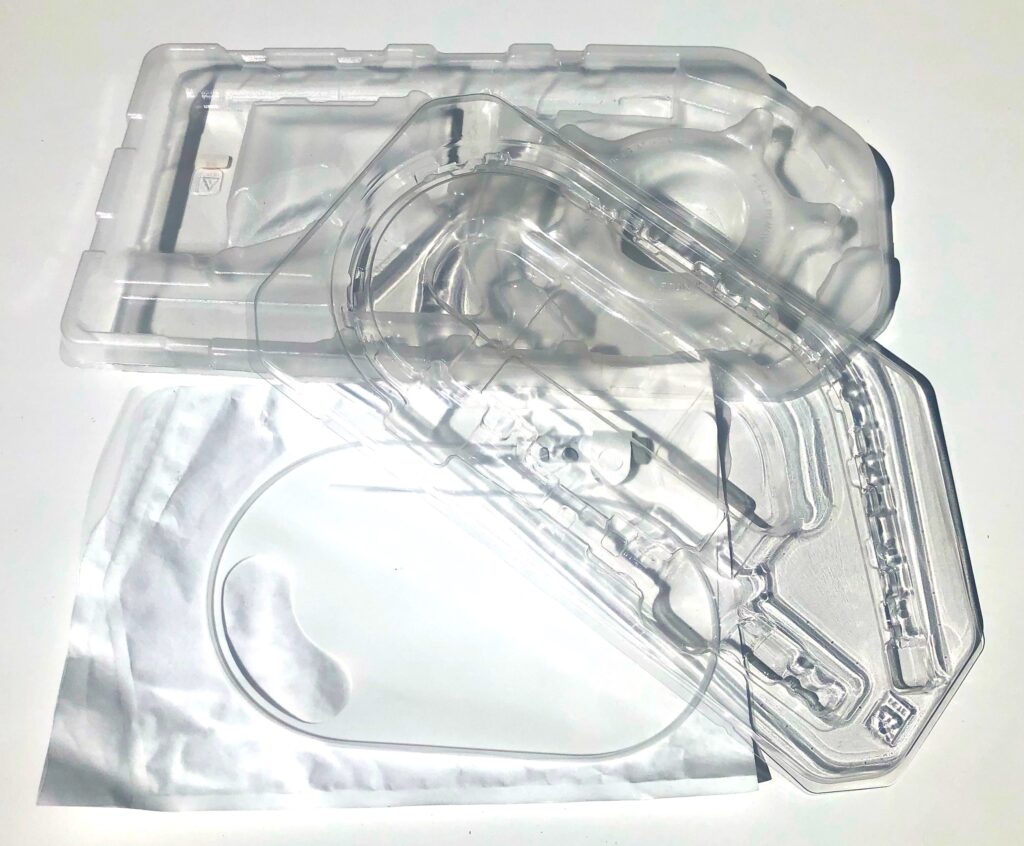

4. Don’t forget about the box.

I have seen it all too often; an organization is so excited to get their product to market but has neglected to fully appreciate how much work is required to put it into a box. Device packaging can take a lot of time and thought, needing to consider sterilization, point of use environments, safe shipping, and shelf storage. There can end up being a need for a vacuum formed tray, permeable heat-sealed bag or two, a shelf box, a shipping carton, accessory organizer compartment, etc. A lot of coordination with the various vendors is often required. When the packaging is left to the end, a lot of time and energy is expended to keep it from being a bottleneck.

A good strategy is to adopt a realistic budget for materials and resources for the packaging early in the project. The packaging should be viewed as a stepwise development process just like the device itself. As the product is being architected, the process of envisioning how the device will be opened and used in the medical setting can start to evolve. A prototype package developed for transporting the protype device will quickly earn its keep if it protects the precious cargo in transit to a test or study facility. Valuable learning will also be obtained and inform the final packaging design.

5. Listen carefully to your medical specialist, (but a little filtering can help).

I remember a situation where a remarkably gifted surgeon was using a prototype catheter I developed. During the study procedure he casually remarked that it would be “nice” if the “fiddly bits” (various tubing connections) could be moved to the other side of the catheter handle. As the principal investigator his word was considered golden, and I was promptly given the mandate by my management; “move the fiddly bits”.

After an accelerated prototype turn and considerable effort on my part, we were back in the operatory in a few months. The newly revised catheter handle was presented to the surgeon. His response, “It’s Ok. It could have stayed the way it was.” The moral to the story is to ‘ask twice before you act once’.

The insights from the medical advisors are of course indispensable but it becomes even more fruitful if challenged or even better have the doctors or investigators discuss the procedure and device among themselves. Be the fly-on-wall for these discussions and you will learn so much more than from an individual contributor.

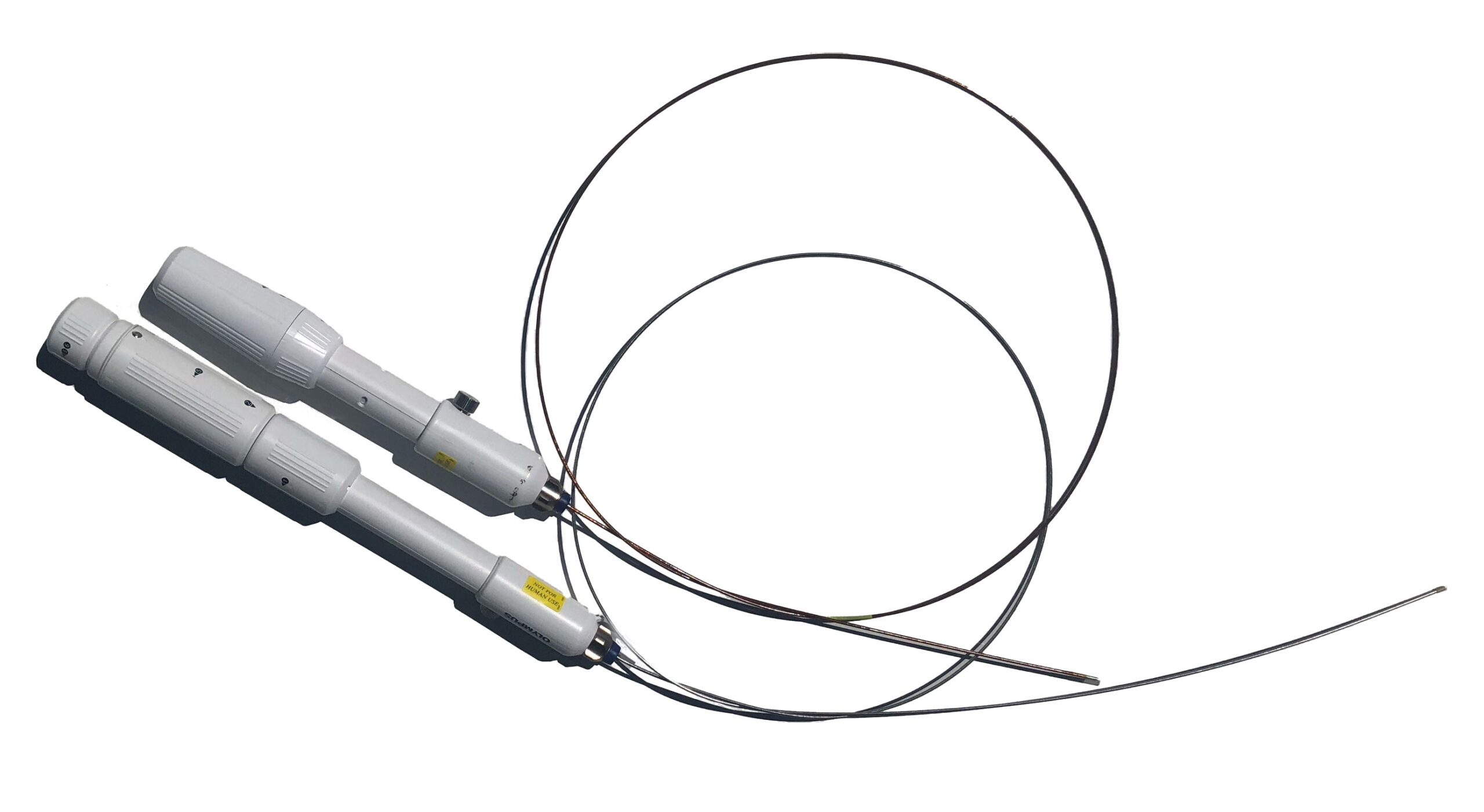

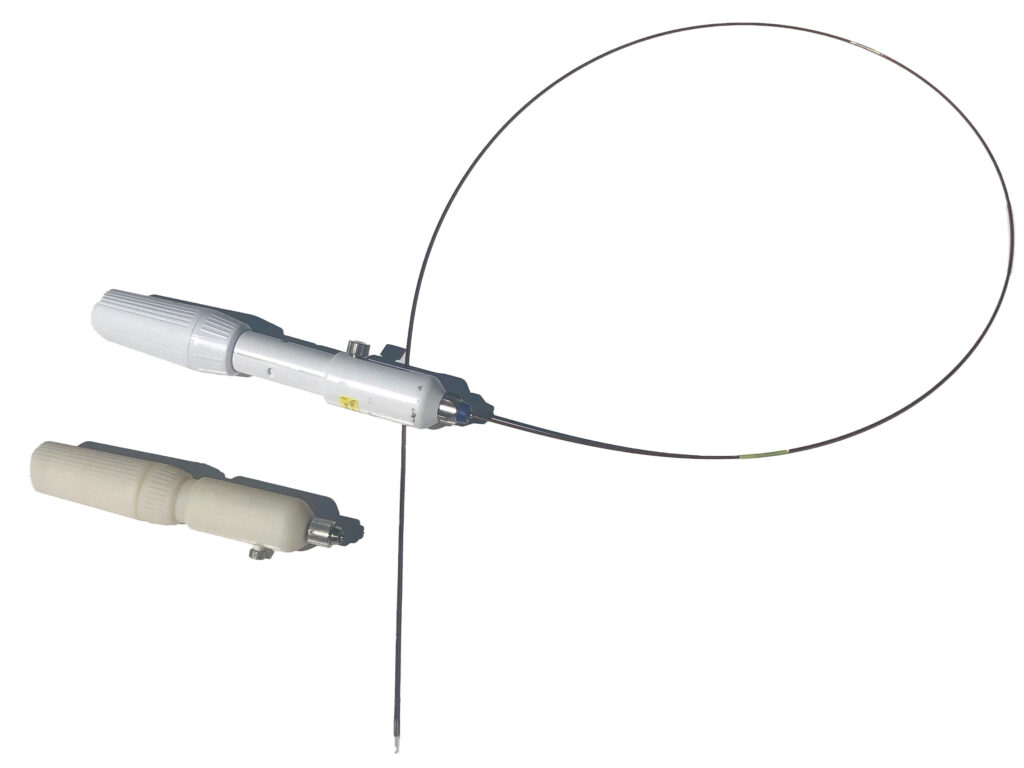

6. Medical devices can be deceptively tricky to design.

There can be all kinds of competing requirements for a device; for instance, consider catheter shafts. Design choices for shafts must consider buckling resistance, torsional rigidity, pushability, trackability, radiopaque observability to name a few. They can require special liners, braiding, jackets of multiple materials among other constructions. There are also usually at least one set of competing requirements that need to be worked through, such as shaft torqueable while maintaining flexibility.

Sometimes the feature set falls into place, but it usually requires a few iterations of careful design, build, and test cycles. A well-conceived handle (hub) design and wise shaft choices can help simplify some requirements but there is no substitute for a good relationship between the vendor and the design team. You never know how complicated a “simple tube” can become.

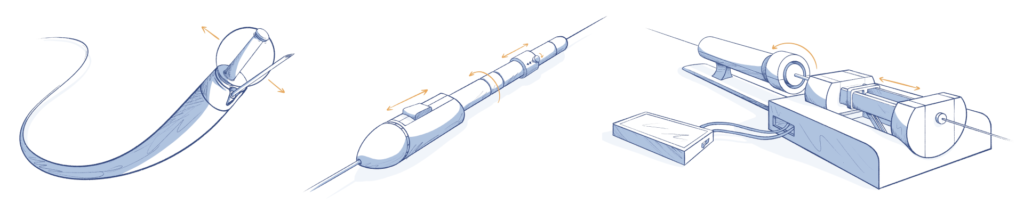

7. Idea Competition is Darwinian fun and early device development’s best friend.

Medical devices can be very tricky to design because human anatomy is so amazingly unique and usually presents some unexpected challenges. Fortunately design engineers love design challenges. We often start by conducting brainstorming meetings. These can become like a great jazz session where we will start to riff on each other’s ideas and take them to different conclusions or radically different directions. The ideation process continues by evolving the ideas, organizing them, and eventually filtering them down to a few solid concepts.

This is where the real fun can truly begin; the concepts are evaluated to see if there is a winner! A champion for each idea is enabled to build a crude but functional proof-of-concept model. The models are then subjected to a side-by-side functional test in sort of a geeky thunder-dome competition. If there is a clear winner, then great. If all concepts are failures, you have most likely uncovered a clue on how to overcome the fundamental issue and the process is repeated. It is product evolution at its earliest and most important phase.

8. A visit to the meat department is a lot cheaper than animal models.

Wow, animal studies can be expensive and rightfully so! The medical product development community undertakes these with only the greatest of care. Besides the preeminent concerns of animal welfare, ethical and moral conduct, there is the added cost of planning, purchasing, and staging for a study. Alternatives such as synthetic tissues or CAD modeling usually fall short of providing experimental feedback that can direct your research in the right path.

Perhaps you should consider a quick stop at the meat department of your local grocery store. I can think of projects in which beef livers, swine blood and chicken skin have been used to guide early-stage device development. Yeah, right, chicken skin? It made a great substitute for duodenum lining in the development of a tunneling device. It is soft, slippery, and stretchy yet tough and hard to slice. What better way to further honor an animal’s life than to use the less desirable meat products to advance medical science?

9. Own your secret sauce recipe, consider using partners for mixing and bottling.

I have visited organizations with incredibly bright people developing some remarkable technologies only to find that the essence of their groundbreaking science is jotted down on note cards. The most successful firms who get their products to market know their core technology, have it well characterized and thoughtfully documented. It makes product development more efficient.

But it is a tricky game; spend too much time on “science” and you are late to market, but push too fast and you will end up redefining your device or instrument during the product design process. The latter can be expensive, disruptive, and still make you late. Another pitfall is for an organization to presume it can offer up its home-grown lab breadboard as a sellable product with just a tweak or two.

An excellent product development group can plug into your development cycle and help where needed. If your project is in the early stage, we can design and deliver with little overhead a highly capable development platform to assist your discovery efforts. If your science is already “baked” we can pick up the ball and get you over the goal line. It takes more than just a few tweaks to get that breadboard, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and FDA compliant as well Underwriters Laboratories (UL) or Conformité Européene (CE) certified.

10. Read the other guys’ “Top 10 Tips” as well.

Choose a quality product development firm that has experience developing many medical and life science instruments. They should be ISO 13485:2016 Certified and know their way around Design History Files (DHFs), risk hazard analysis, and verification planning and execution.

Learning from others’ past experience designing medical devices can be invaluable. Reading various PDF’s, whitepapers, and blogs will give you unique insights to consider with a number of great tips from different perspectives.

If you are designing an innovative product and need help understanding the medical device development space and the unique requirements that must be met to achieve success, contact us to learn more about our medical device development capabilities.