The prototyping process is faster and easier than ever before. The Maker Movement encourages us to build, build, build. Rapid prototyping with Arduino and 3D-printed parts and overnight shipping from McMaster-Carr and Digi-Key enable engineers to quickly prove out concepts. The resulting tangible objects can validate a critical functionality or communicate a design intent.

Equally important, you can show your prototypes to prospective customers who will give you valuable feedback on usability, shape, size, weight, and much more. But is there such a thing as too much prototyping? We think so.

Mathematics in product development

Simplexity’s “7 Steps to Simplification©” include some mainstays of product development, such as the iterative cycle of brainstorming, designing, prototyping, and testing. If there is one step that raises eyebrows, it’s “Do the Math.” Really? Who needs math?

Although we love rapid prototyping, we believe a little engineering calculation and analysis can sometimes save even more time and money. At times, simple hand calculations are sufficient to verify part sizing and strength, maximum allowable current, or maximum download speed. Other problems, such as correct motor sizing and gear train analysis, call for more involved calculations.

Sometimes, computer-based simulations, like finite element analysis (FEA) and computational fluid dynamics (CFD), provide insights that cut down on the number of physical iterations required.

Balance making and engineering

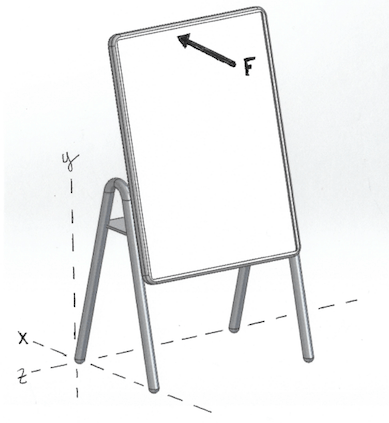

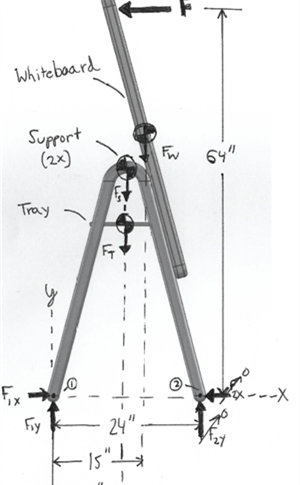

Here is a simple example from when I was working at a previous company who took a different approach. We were designing a four-legged easel for whiteboards. We needed to know what writing force could be applied to the top of the whiteboard before the easel would tip over. Two approaches were taken in parallel.

Since they had a strong tradition of prototyping, their machine shop went about carefully prototyping the easel with the correct materials and geometry. They used a force gauge to measure the push force required to tip the easel. After one week of prototyping, they had their result.

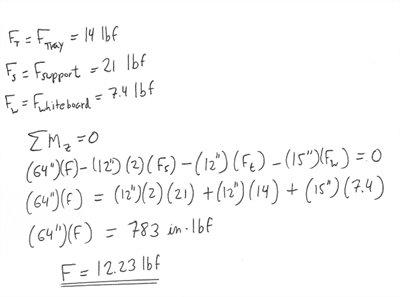

Meanwhile, I took the “Do the Math” approach and used statics to calculate the force value. The results of the prototyping matched the calculated result (about 12 pounds). Yet the calculations only took one hour to complete.

Doing the math leads to expectations of how an object will behave. Rapid prototyping complements the analysis results by verifying or disproving the expected behavior. This in turn leads to faster and better decisions on the path to launching a successful product. To truly be agile at product development, we strive to find a balance between making and engineering.

Would you like to see how our approach to product development can help you with your first prototype? Contact Simplexity today.